Why Your Heels Don't Touch in Downward Dog (And Why That's Okay)

Your heels don't touch in downward dog because of one or more of three factors: calf muscle length, ligament restrictions, or your unique bone structure at the ankle joint. And here's the reassuring truth I share with every yoga teacher I train: it's completely okay if your heels never touch the ground.

As a Doctor of Physical Therapy who has practiced yoga for over 20 years, I can tell you something that might surprise you: my heels still don't touch the ground in downward dog. Not because I haven't practiced enough. Not because I'm doing it wrong. But because of my individual anatomy. And honestly? I've made my peace with it. I'm still a great yoga teacher, and a pretty good wife too.

Understanding why this happens transforms how you experience and teach this foundational posture.

In This Article:

The anatomy behind your heels in downward dog

3 Factors that contribute to your heels not touching the ground

Factor 1: Muscle length restrictions

Factor 2: Ligament restrictions

Factor 3: Bone structure

What this means for your practice and teaching

The Anatomy Behind Your Heels in Downward Dog

To understand why heels don't touch in downward dog, we need to look at what's happening at the ankle.

In downward dog, your ankles are in dorsiflexion. The angle at the front of the ankle gets smaller while the angle at the back gets bigger. Think of it like closing a door most of the way at the front while the back of the door swings open wider.

This means the tissues at the back of your ankle including your calf muscles, ligaments, and even your bones, have to accommodate this expanding angle. When any of these structures reach their limit, your heels stay lifted.

Let's look at each factor.

Factor 1: Calf Muscle Length

The most common reason heels don't reach the floor in downward dog is the length of your calf muscles, specifically the gastrocnemius and soleus.

These muscles run down the back of your lower leg and connect to your heel bone through the Achilles tendon (a term you've probably heard before even if you've never thought much about where it actually is). When your ankles move into dorsiflexion, these muscles have to lengthen to allow your heel to drop.

Curious about how muscles lengthen and shorten? Read Muscle Contractions in Yoga: The 3 Types You Need to Know.

If your calf muscles resist elongation, they'll limit how far your ankle can dorsiflex and your heels stay lifted.

Here's where it gets interesting: with consistent practice, muscle length can change over time. This is why some people notice their heels gradually getting closer to the floor after months or years of practice. The body adapts.

But muscle length isn't the only factor at play.

Factor 2: Ligament Restrictions

Bones connect to each other through ligaments, and ligaments have a very important job: limiting excessive mobility to keep your joints stable.

For some people, even when the muscles have the ability to lengthen, the ligaments reach their end range first and stop the movement. This is your body's protective mechanism.

Here's something important to understand: you don't want to stretch ligaments too far. When ligaments overstretch, they lose their ability to stabilize the joint. I'd rather have stable, functional ankles than heels touching the floor in downward dog. Wouldn't you?

Factor 3: Bone Structure

This is the factor that surprises most people and what I think is really cool: it means you can stop blaming yourself!

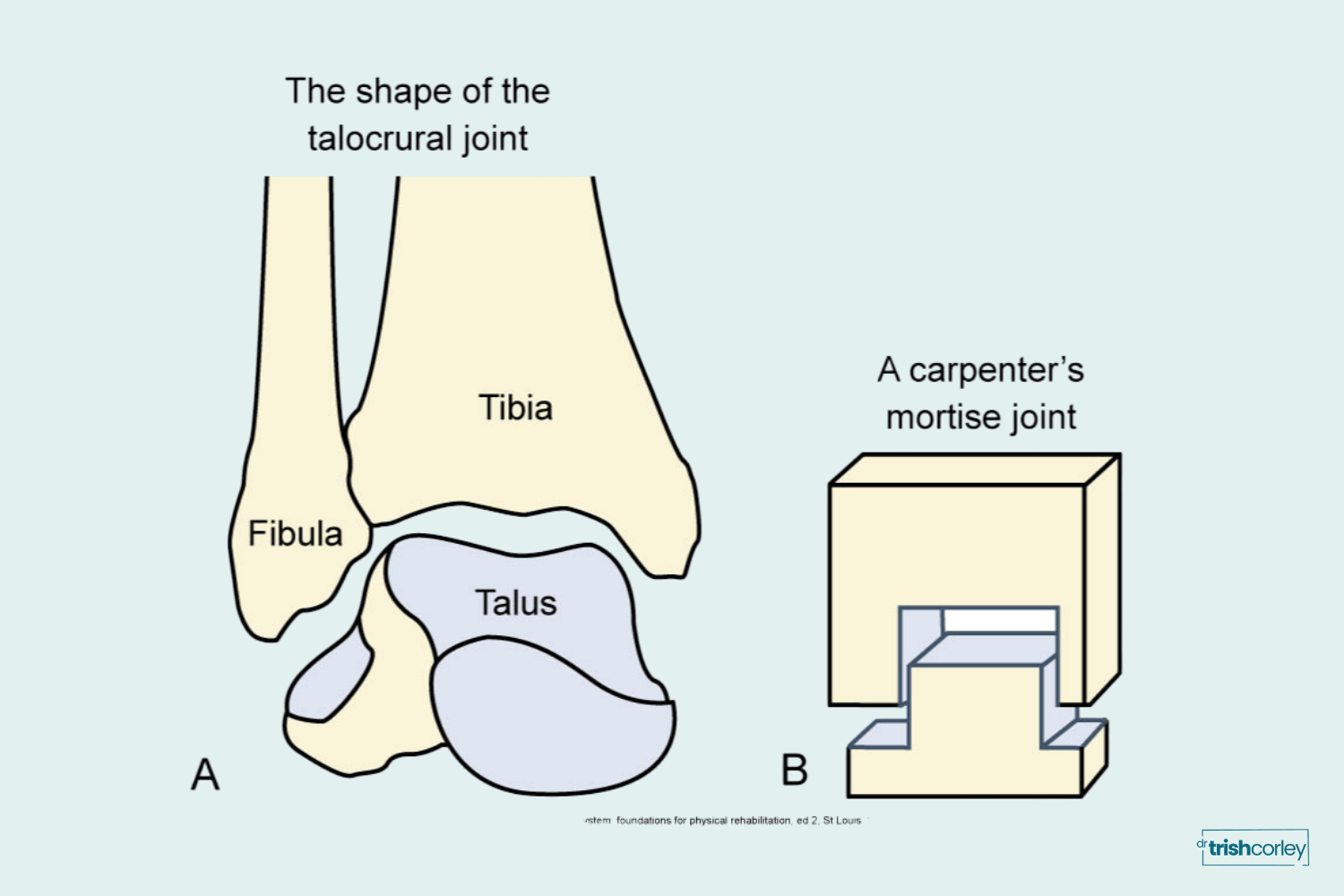

The ankle joint is formed by three bones: the tibia and fibula (your shin bones) and the talus (the bone that sits on top of your heel bone). The tibia and fibula create a shape that allows the talus to rest beneath them, similar to a carpenter's mortise joint.

When you move into dorsiflexion, the tibia and fibula move forward over the talus. At some point, bone meets bone. And that's your end range.

Here's what makes this personal: everyone's bones are shaped differently. Variations in the shape of your talus or the angle of your tibia and fibula directly influence how much dorsiflexion is available to you. Someone with a larger talus may experience bone-on-bone contact much sooner than someone with a smaller talus.

If bone structure is limiting your dorsiflexion, no amount of stretching will change it. Your heels will stay lifted—and that's perfectly fine.

What This Means for Your Practice

Understanding this anatomy is empowering because it shifts the focus from "fixing" your downward dog to working with your body as it is.

Instead of forcing your heels down (which could compromise ankle stability or create misalignment elsewhere), focus on what you can control:

Press through all four corners of your feet

Engage your legs

Lengthen your spine

Breathe

You'll receive all the benefits of the posture whether your heels touch or not.

What This Means for Teaching

If you teach yoga, this anatomy knowledge changes how you cue and how you respond to students.

Rather than saying "one day your heels will touch" (which may or may not be true) try something like:

"It's okay if your heels aren't on the ground. Press through the four corners of your feet and find length in your spine. You're getting all the benefits right here."

This kind of anatomy-informed cueing builds trust with your students. They feel seen and understood rather than like they're failing at a "basic" posture. This is exactly what I cover in depth in my Enlightened Anatomy Course. Understand the "why" behind alignment so you can cue with genuine confidence. Because when you understand anatomy, you stop guessing and start teaching from a place of real knowledge. And that changes everything.

Get Curious! Q&A

Will my heels eventually touch the ground with more practice?

Maybe, or maybe not. If calf muscle tightness is the limiting factor, consistent practice may gradually increase your range of motion. However, if ligaments or bone structure are the limiting factors, your heels may never touch, regardless of how long you practice. Both outcomes are completely normal.

Should I use a prop under my heels in downward dog?

Props can be helpful for comfort, but they're not necessary. If having something under your heels helps you focus on other aspects of the posture like spinal length or shoulder alignment, go for it. Just know that using a prop won't "fix" anything that needs fixing, because nothing is broken.

Does it mean I'm doing downward dog wrong if my heels don't touch?

Absolutely not. Heel position is determined by your individual anatomy, not by how well you're performing the posture. Rather than focusing on a heel position that may or may not be available to your body, focus on alignment changes you can control such grounding through your hands and restoring the natural curves of the spine.

What muscles affect heel position in downward dog?

The primary muscles are the gastrocnemius and soleu. These are your calf muscles. These muscles must lengthen to allow the ankle to dorsiflex and the heels to lower. The tibialis anterior (front of the shin) also plays a role by actively drawing the top of the foot toward the shin.

How can I tell if it's tight muscles or bone structure limiting my heels?

This can be tricky to determine on your own. Generally, if you feel a stretching sensation in your calves, muscle length is likely a factor. If you feel a hard "block" or pinching at the front of your ankle with no stretch sensation in the back, bone structure may be the limitation. A physical therapist or movement professional can help you assess this more precisely.

Where can I learn more about yoga anatomy?

Start with my Yoga Anatomy for Teachers Guide, which covers the foundations every teacher needs.

Learn the Anatomy That Transforms Your Teaching

Understanding why your heels don't touch the ground is just the beginning. The feet are your foundation in every standing posture — and how you cue them changes everything.

Want to learn 3 anatomy-informed foot cues that create stability and grounding in any standing yoga posture? Get my free Cue with Confidence guide and see the Balanced Posture Alignment framework in action.